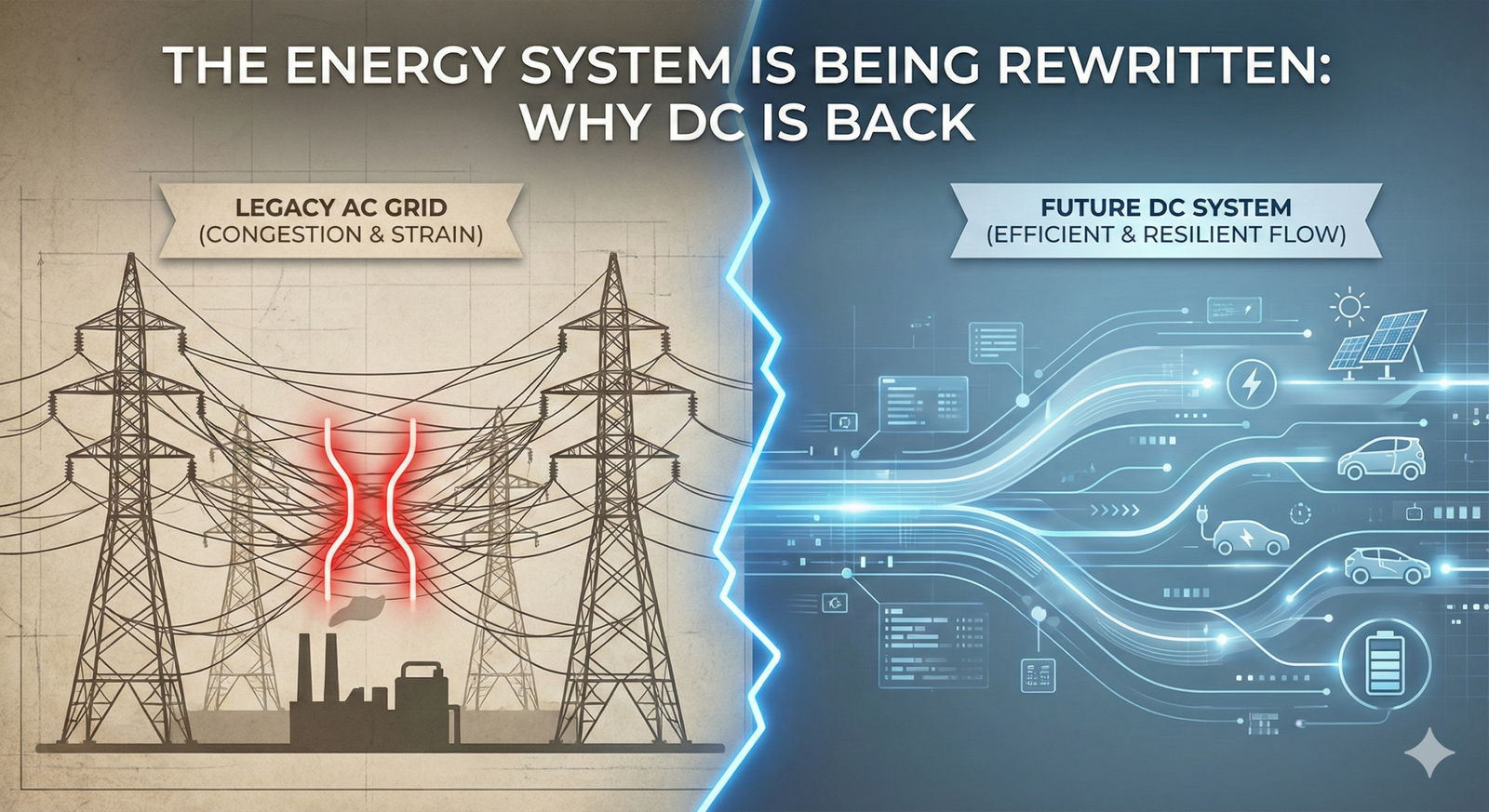

For more than a century, alternating current (AC) has been the backbone of global electricity systems. It enabled long-distance transmission, supported national grids, and powered industrial growth. But the conditions that made AC dominant are no longer the conditions shaping energy demand today.

“The global energy system is being rewritten. Not incrementally, but structurally.”Steve Halewood

Electric vehicles, battery storage, renewable generation, and digital infrastructure are changing not just how much energy we use, but how energy flows, where it is managed, and what it is expected to do. In that context, Direct Current (DC) is not making a comeback as a historical curiosity—it is re-emerging as a foundational architecture for modern energy systems.

This shift is not ideological. It is practical.

Why the Legacy AC Model Is Under Strain

AC was optimised for a world of:

-

Centralised generation

-

One-way power flow

-

Predictable, steady demand

-

Minimal local control

That model worked when energy systems were largely passive. Power was generated centrally, transmitted over distance, and consumed by relatively static loads.

Today’s energy landscape looks very different.

Modern demand is dynamic and decentralised

-

EV charging introduces large, coincident, time-sensitive loads

-

Batteries charge and discharge daily

-

Renewables generate intermittently, not on demand

-

Digital systems require continuous, high-quality power

The grid is now expected to balance variability, not just deliver capacity. Much of the strain we see—connection delays, reinforcement costs, congestion—is a symptom of architectures being asked to do things they were never designed for.

This is not a failure of the grid. It is a mismatch between legacy design assumptions and modern use cases.

The Quiet Return of DC Power

DC never disappeared. It simply moved into places where reliability, efficiency, and control mattered most.

Data centres, telecommunications networks, battery systems, electronics, and transport have all relied on DC for decades. What has changed is scale.

Modern energy assets are DC by nature

-

Solar PV generates DC

-

Batteries store and release DC

-

EVs charge and operate on DC internally

-

Digital infrastructure runs exclusively on DC

In traditional AC-centric systems, these assets must constantly convert energy back and forth between AC and DC. Each conversion adds:

-

Energy loss

-

Heat

-

Component complexity

-

Failure risk

As systems become more dynamic and interconnected, these inefficiencies compound.

DC is not re-emerging because it is new. It is re-emerging because it aligns naturally with how modern energy assets behave.

DC as a System Architecture, Not a Component Choice

One of the most common misconceptions is that DC is simply an efficiency upgrade. In reality, its significance is architectural.

Fewer conversions, fewer failure points

DC-centric systems:

-

Reduce the number of power electronic stages

-

Shorten energy paths

-

Simplify protection and control

This leads to systems that are not just more efficient, but more predictable and easier to manage.

Simpler control enables smarter systems

AC systems require software to manage:

-

Frequency

-

Phase synchronisation

-

Reactive power

DC systems remove these variables. That makes them:

-

Easier to optimise

-

Faster to respond

-

Better suited to software-defined control

As energy systems become increasingly automated, predictability becomes as important as capacity.

Where DC Is Already Dominating

DC is not a future concept. It is already dominant in several critical sectors.

EV charging infrastructure

High-power EV charging exposes the limits of grid-only AC architectures. Charging demand is peaky, concurrent, and time-sensitive.

DC-centric charging systems:

-

Buffer grid demand using local storage

-

Decouple charger performance from grid constraints

-

Enable grid-aware, flexible charging at scale

This is why many successful charging deployments now treat DC as the internal backbone, with AC used primarily at the grid interface.

Battery energy storage systems

Batteries are DC assets. Their performance, efficiency, and lifespan are heavily influenced by how they are integrated.

DC-coupled storage:

-

Improves round-trip efficiency

-

Reduces thermal stress

-

Enables faster, more precise control

As storage shifts from backup to active system optimisation, architectural alignment becomes critical.

Renewable integration

Solar PV produces DC energy, yet is often forced through multiple AC conversions before being used or stored.

DC-centric renewable systems:

-

Increase self-consumption

-

Reduce curtailment

-

Improve integration with storage and charging

This turns renewables from passive generators into active system inputs.

Data centres and digital infrastructure

Data centres have long favoured DC internally because:

-

Digital equipment requires DC

-

Power quality is critical

-

Downtime is unacceptable

As energy systems become more digital and software-driven, they begin to resemble data centres in their control and reliability requirements. The same architectural logic applies.

Behind the Meter: Where the Shift Is Happening Fastest

The most significant DC adoption is happening behind the meter—inside sites, campuses, depots, and facilities.

Behind-the-meter systems:

-

Concentrate storage, charging, renewables, and control

-

Allow architectural choice independent of grid standards

-

Deliver immediate efficiency and resilience benefits

This is where DC delivers the strongest value proposition: not as a grid replacement, but as a local optimisation layer.

The Hybrid AC–DC Future

The future energy system is not AC or DC. It is hybrid.

AC still matters

-

Long-distance transmission

-

Utility interoperability

-

Standardised grid exchange

DC is becoming the system core

-

Local distribution

-

Storage and charging

-

Renewable integration

-

Digital control

In practice, this means:

-

AC at the boundary

-

DC inside the system

Hybrid AC–DC architectures allow organisations to:

-

Retain existing infrastructure

-

Deploy DC incrementally

-

Scale without constant redesign

This is a pragmatic evolution, not a disruptive overhaul.

Why This Matters for Infrastructure Decisions Today

Energy infrastructure decisions have long lifespans. Choices made now will shape operational performance for decades.

Organisations investing in:

-

EV charging

-

Battery storage

-

Renewable generation

-

Smart energy systems

must consider not just capacity, but architectural alignment.

DC-centric design:

-

Preserves optionality

-

Improves long-term efficiency

-

Enables future software-driven optimisation

This is increasingly why DC-first thinking is moving from specialist applications into mainstream infrastructure planning.

DC Is Not a Trend. It Is a Correction.

DC is not “back” because the industry is nostalgic. It is back because the assumptions that made AC dominant no longer hold everywhere.

Modern energy systems are:

-

Local

-

Dynamic

-

Digital

-

Actively managed

DC provides a simpler, more efficient foundation for that reality.

At GridUnlock, this shift underpins how we think about energy architecture: not as isolated technologies, but as coherent systems designed around how energy is actually generated, stored, and used.

The energy system is being rewritten.

DC is not replacing AC—but it is redefining what modern energy infrastructure looks like.

And that rewrite has already begun.

To get our 15 Part White Paper on ‘Why DC is the Future’, Subscribe to our email;